Researchers have found that a high-fat diet increases the metabolism of fructose in the small intestine, resulting in a fructose-specific metabolite known as glycerate released into circulation. The circulating glycerate can then result in damage to the pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin, which increases the likelihood of glucose tolerance diseases like Type 2 diabetes.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE

DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.05.007

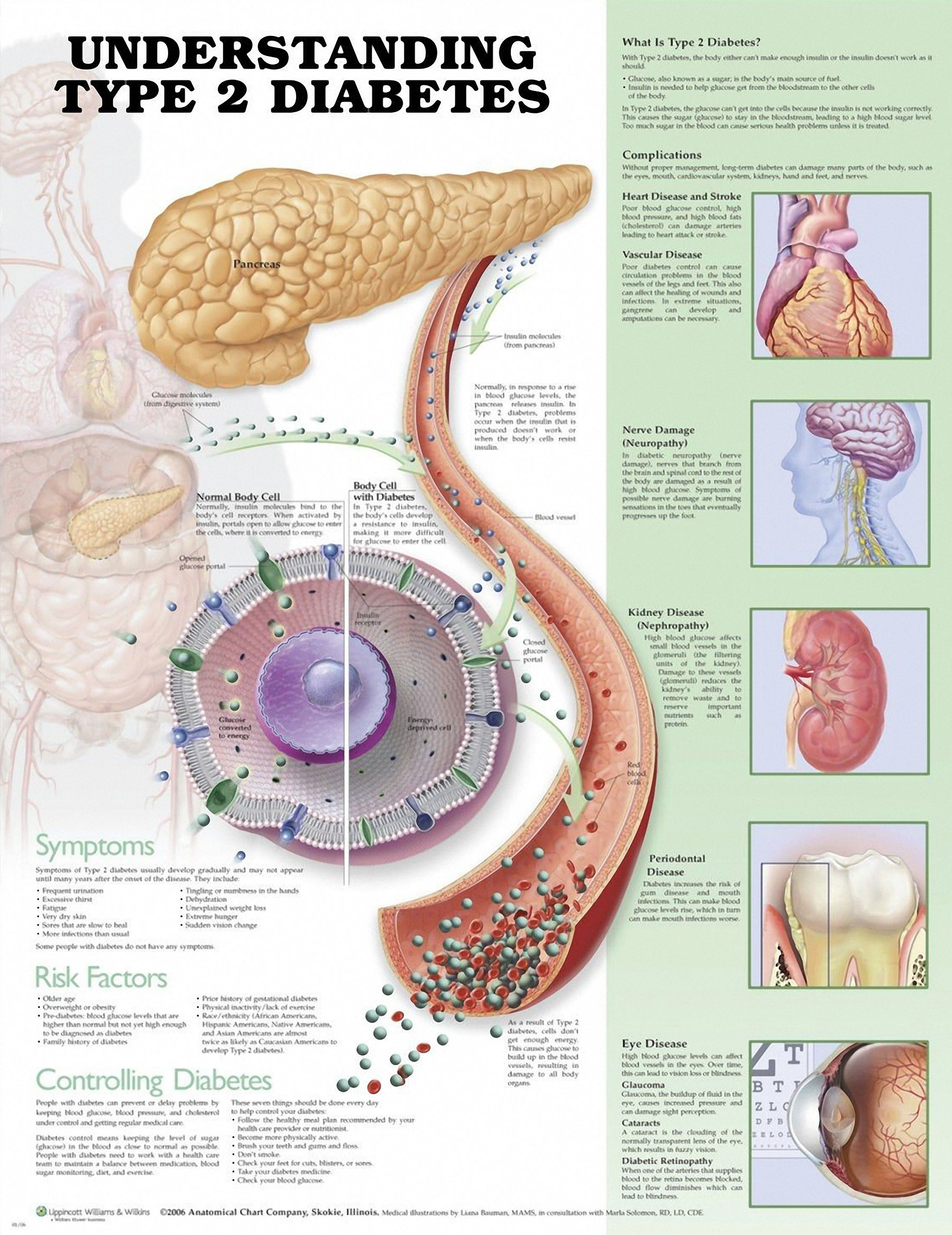

Even though Type 2 diabetes is generally found in older individuals, it’s been happening increasingly more in younger individuals. The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes has doubled in the past 20 years alone. Of equal concern are the health risks linked to Type 2 diabetes, which include stroke and heart disease.

In Type 2 diabetes, there are inadequate insulin levels, a hormone regulating the flow of glucose into peripheral cells. This typically happens because of insulin resistance, which is when peripheral tissues don’t have a normal response to insulin and absorb less glucose. The pancreas works overtime to secrete more insulin to compensate for this and eventually loses this ability. This results in an unhealthy glucose accumulation in the blood.

Many studies have been carried out with regards to how high fat and fructose diets influence Type 2 diabetes development. Previous studies have found that fructose produces harmful effects in the liver. Other research has however revealed that these effects are usually prevented by the metabolism of fructose in the small intestine; the liver only takes part in the metabolic process when levels of fructose are excessive.

These observations impelled the researchers to explore the metabolism of fructose in the small intestine to establish its role in Type 2 diabetes development. Experiments in mice consuming a high-fat diet along with corresponding amounts of sugar led to higher metabolism of fructose in the small intestine. This increased production of glycerate in the small intestine was subsequently released and circulated in the blood. This indicates that the metabolism of fructose in the small intestine is increased by a high-fat diet which increases the production of circulating glycerate.

More evidence for the role of glycerate in diabetes was discovered when the researchers looked at data from patients exhibiting abnormally high levels of circulating glycerate who have a disease known as D-glycerate aciduria. The analysis showed that this abnormality presented an independent and significant diabetes risk factor for these individuals. More tests were carried out to evaluate the impact of circulating glycerate and fructose-fed to normal as well as high-fat diet mice.

The results suggested that the glucose impairments observed in the mice that had been injected with glycerate were because of a reduction in circulating insulin, as opposed to insulin resistance. Histologic analysis verified reduced numbers and increased deaths of the beta cells producing insulin in pancreatic islet regions in the mice that had been injected with glycerate, leading to reduced insulin levels.

The study results collectively indicate that extended exposure to high glycerate levels because of excessive consumption of dietary fat and fructose-rich diets increases the risk of pancreatic islet cell damage and diabetes.