Research has found that individuals imagining to be a thief who scouted a virtual art museum to prepare for a heist had better memory of the paintings they had seen in comparison to individuals playing the same computer game who were carrying out the heist immediately.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2304881120

These subtle motivation differences, urgent and immediate goal-seeking as opposed to curious future goal exploration, have tremendous potential for dealing with real-world challenges like treating psychiatric disorders.

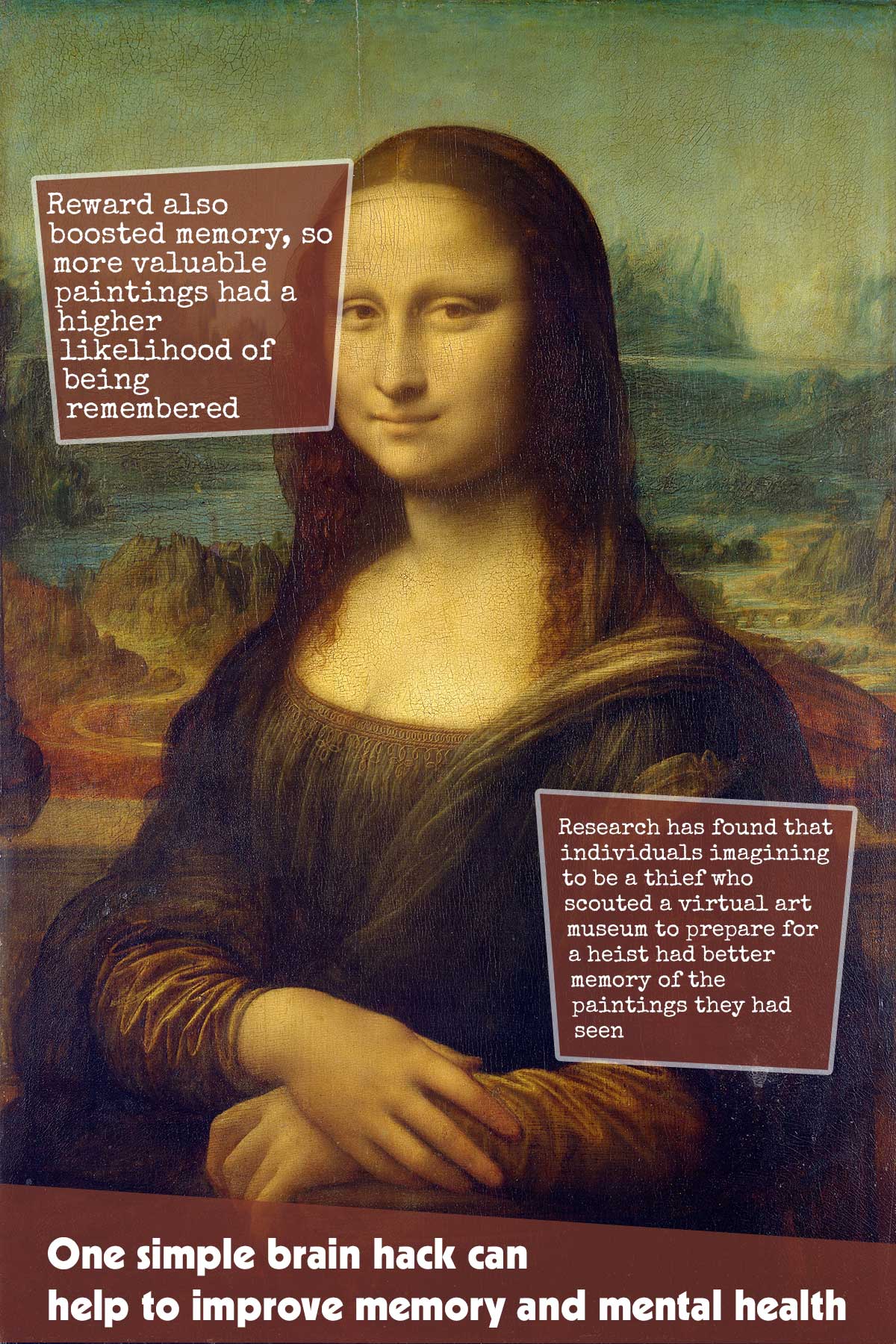

The researchers recruited 420 individuals to pretend to be virtual art thieves for one day. The individuals were then randomly allocated to 1 of 2 groups and were given different backstories.

The individuals in the urgent group were told they were master thieves carrying out the heist immediately and they were to steal as much as they could. The individuals in the curious group were told they were thieves who were scouting the museum to plan a heist in the future.

However, after these different backstories were given to them, the individuals in the 2 groups played the identical computer game and scored the identical way. An art museum was explored with 4 colored doors that were clicked on that represented different rooms that revealed a painting from the room as well as its value.

More valuable art collections were held in some of the rooms. Regardless of which scenario the participants pretended to be in, real bonus money was earned by all of them from acquiring more valuable paintings.

The impact of this mindset difference was most evident the next day. When individuals logged back into the game, they were presented with a pop quiz about whether 175 different paintings could be identified (75 new paintings and 100 from the previous day). If a painting was flagged as familiar, the participants had to remember how much it was worth as well.

The individuals in the curious group who imagined preparing for a heist had better memory the following day. More paintings were correctly recognized and the value of each painting was remembered. Reward also boosted memory, so more valuable paintings had a higher likelihood of being remembered. The individuals in the urgent group who imagined carrying out the heist did not experience this.

The individuals in the urgent group experienced a different advantage though. They could determine which doors hid more valuable pieces better, and as a result, grabbed paintings with a higher value. Their collection was evaluated at about $230 more compared to the collection of the individuals in the curious group.

Although, the difference in strategies (urgent as opposed to curious) and their outcomes (higher-valued paintings as opposed to better memory) doesn’t mean one is superior to the other. It’s useful to learn which approach is adaptive for a given moment and make use of it smartly.

For instance, an urgent, high-pressure approach may be the best choice for a short-term problem. If out hiking and s a bear is encountered, long-term planning is not going to be useful, the focus will be to get out of the situation immediately. An urgent mindset option may also be useful in less life-threatening scenarios that require short-term focus.

Sometimes it’s useful for individuals to be motivated to find information and remember it, which could have longer-term lifestyle change consequences. And for that, a curious approach would need to be chosen so that information can be retained.