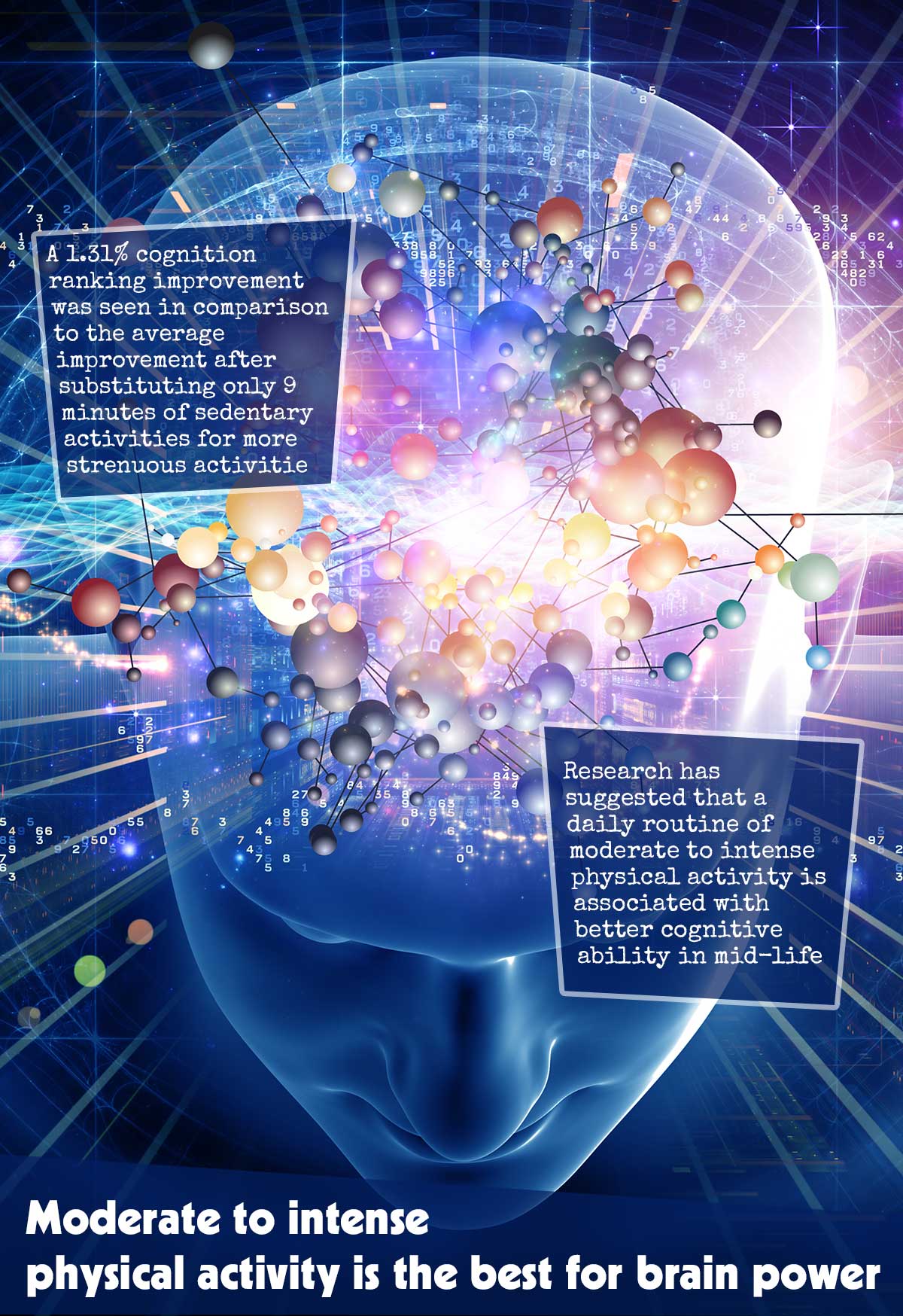

Research has suggested that a daily routine of moderate to intense physical activity is associated with better cognitive ability in mid-life.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE DOI: 10.1136/jech-2022-219829

According to the findings, moderate to intense physical activity is the best kind of activity for working memory as well as mental processes such as organization and planning. Replacing it with 6 to 7 daily minutes of sedentary behavior or light-intensity exercise can result in weaker cognitive performance.

Previous research has often shown the health benefits of regular moderate to intense physical activity, but not many have considered sleeping time as well, being the largest portion in a 24-hour day period.

To find out if moderate to intense physical activity, in relation to all other types of daily activity behaviors, would be the most beneficial for mid-life cognitive performance, they decided to take a compositional approach.

The study included 8581 participants from the 1970 British Cohort Study between the ages of 46 and 47 whose health was tracked during childhood and adulthood.

Participants were asked to answer detailed questionnaires about their health, background, and daily lifestyle. They were also asked to wear an activity tracker for 10 hours a day over a period of 7 days.

To measure verbal memory and executive function, participants were given a series of cognitive tests. This included tasks for immediate and delayed word recall, verbal fluency, and processing speed/accuracy. Results from each test were then combined to form the overall global scores for memory and executive function.

A total of 2959 participants, who had previously agreed to wear an activity tracker, were excluded from the study due to device error, not wearing it long enough, or not fully completing the questionnaires.

The final analysis consisted of 4,481 individuals, with slightly more than half being female. Two-thirds of the participants were married and 43% held some form of education till 18 years. Additionally, more than two-thirds were non-risky or occasional drinkers and 50% had never smoked.

According to the results derived from activity tracker data, individuals reported spending 51 minutes on moderate to intense physical activities, 9 hours and 16 minutes on sedentary behaviors, 5 hours and 42 minutes on light-intensity physical activities, and 8 hours and 11 minutes sleeping per 24-hour period.

Results indicated that more time spent engaging in moderate to intense physical activity was associated with better cognitive performance after taking into consideration educational attainment, workplace physical activity, and health issues. However, once controlling for health issues, the relationship between increased physical activity and improved cognitive performance weakened.

Sedentary behavior in relation to light-intensity physical activity and sleep was also positively linked to cognitive performance. This result could be because these activities give people more opportunities for engaging in mentally stimulating activities like reading books or working instead of watching TV. The associations were stronger for executive function than they were for memory.

Individuals with higher cognitive performance scores spent more time engaging in moderate to intense physical activity, while those with lower scores engaged in more light-intensity activities.

To explore the relation between activity and cognition, the researchers changed the amount of time spent on different activities every minute to analyze its influence on overall mental performance scores. This revealed increased scores after moderate to intense physical activity displaced other activities.

A 1.31% cognition ranking improvement was seen in comparison to the average improvement after substituting only 9 minutes of sedentary activities for more strenuous activities, a positive trend that became a lot more prominent with greater sedentary activity reductions.

There was likewise a 1.27% improvement from substituting gentle activities or 1.2% from substituting 7 minutes of sleep. Such improvements revealed additional improvement with longer exchanges of time.

Sedentary behavior was also positive for cognition scores, but only after replacing it with 56 minutes of sleep or 37 minutes of light-intensity physical activity.

Cognition ranking started declining by 1 to 2% after only 8 minutes of more strenuous activity was substituted for sedentary activity. Ranking continued to decrease with greater declines in moderate to intense physical activity.

Substituting vigorous activities with 6 minutes of light-intensity physical activity or 7 minutes of sleep was likewise associated with similar reductions of 1 to 2% in cognition ranking, again declining for greater losses of moderate to intense physical activity.

The activity trackers only registered the time in bed as opposed to sleep quality or duration, which could help to explain the sleep association.

In real terms, moderate to intense physical activity is normally the smallest part of the day, and the most difficult intensity to attain. Possibly because of this, loss of any moderate to intense physical activity time at all seemed to be detrimental.

Because this was an observational study, cause can’t be established. And the researchers point out that context for each movement component can’t be provided from activity tracker measures.

Nevertheless, the researchers conclude that this approach supports an important role for moderate to intense physical activity in cognition support, and efforts should be made to strengthen this component of daily movement.