Research reveals that inadequate sleep in combination with unrestricted food access increases calorie intake and subsequent accumulation of fat, particularly the unhealthy belly fat. Results from the study indicate that inadequate sleep resulted in an increase of 9% in the total area of abdominal fat and an increase of 11% in abdominal visceral fat, in comparison to a control sleep group. Visceral fat is fat deeply deposited inside the abdomen surrounding internal organs which is strongly associated with metabolic and cardiac diseases.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE

DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.038

Inadequate sleep is quite often a behavior of choice, which has become an increasingly pervasive choice. Over a third of individuals in the United States routinely don’t get sufficient sleep, partly because of shift work, as well as using smart devices and social networks during usual times of sleep. People also have a tendency to consume more food when awake for longer hours without an increase in physical activity.

The results demonstrate that shorter sleep, even in healthy and relatively lean young individuals, is linked to a calorie intake increase, a very small weight increase, and a substantial increase in belly fat accumulation.

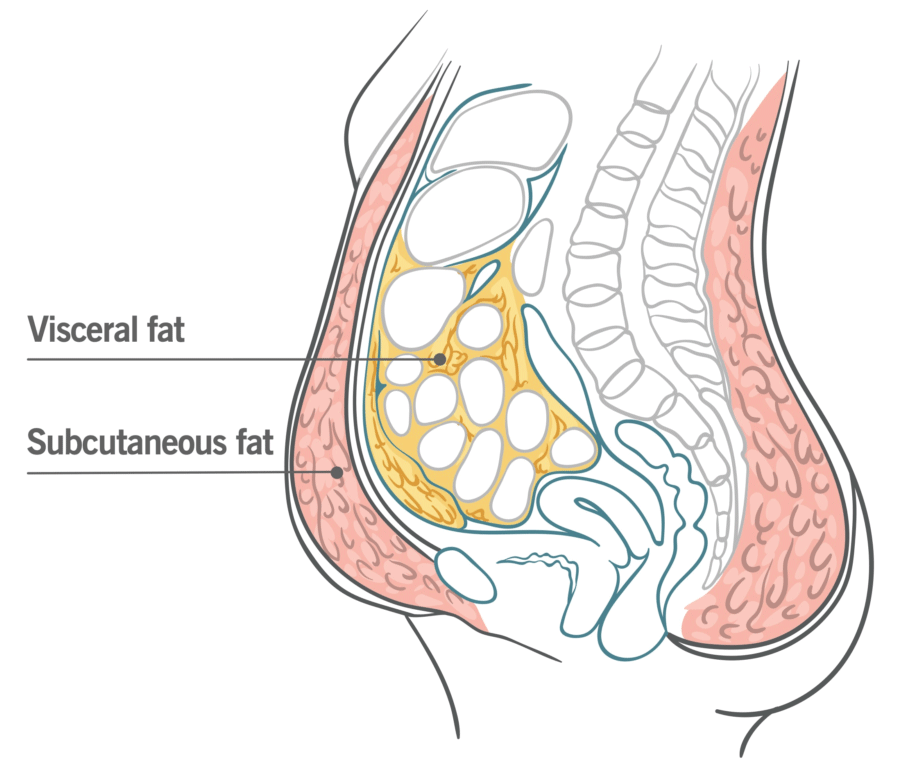

Fat is normally deposited under the skin, or subcutaneously. The lack of sleep however seems to redirect fat to the unhealthier and potentially dangerous visceral area. Also, although there was a calorie intake and weight reduction during recovery sleep, visceral fat carried on increasing.

This indicates that lack of sleep has been an unrecognized visceral fat deposition trigger and that short-term catch-up sleep doesn’t reverse the accumulation of visceral fat. These results implicate long-term lack of sleep as a contributor to the obesity epidemic, as well as metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.

The study consisted of 12 healthy obese-free individuals each participating in two 21-day sessions in an in-patient environment. Following a 3-month washout period, they were randomly allocated to a normal sleep control group or a restricted sleep group for 1 session and the next session the opposite.

Free choice of food was available to each group during the entire study. Circulating appetite biomarkers; fat distribution, which included visceral fat or fat belly; body composition; body weight; energy expenditure; and energy intake were all measured and monitored.

The first 4 days were a period of acclimation during which time all individuals were permitted 9 hours of sleep in a bed. The restricted sleep group was permitted 4 hours of sleep with the control group maintaining at 9 hours of sleep for the subsequent 2 weeks. Both groups then had 3 recovery days and nights with 9 hours in bed.

Over 300 extra daily calories were consumed for the sleep restriction duration, with about 13% more protein and 17% more fat consumed, in comparison to the acclimation stage. The consumption increase was highest in the early sleep deprivation days and then leveled off in the recovery period to starting levels. Energy expenditure remained for the most part the same throughout.

The accumulation of visceral fat was only discovered by CT scan which would have been missed otherwise, particularly since the weight increase was rather modest at approximately 1 pound. Weight measures alone would be incorrectly reassuring with regards to the health consequences of lack of sleep. Also of concern is the potential impact of repeated inadequate sleep periods with regards to progressive and cumulative visceral fat increases over a number of years.