Research has found that adhering to a time-restricted eating regimen that restricts the consumption of food to a maximum 10-hour time frame shows encouraging beneficial metabolic effects in type 2 diabetes individuals.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE

DOI: 10.1007/s00125-022-05752-z

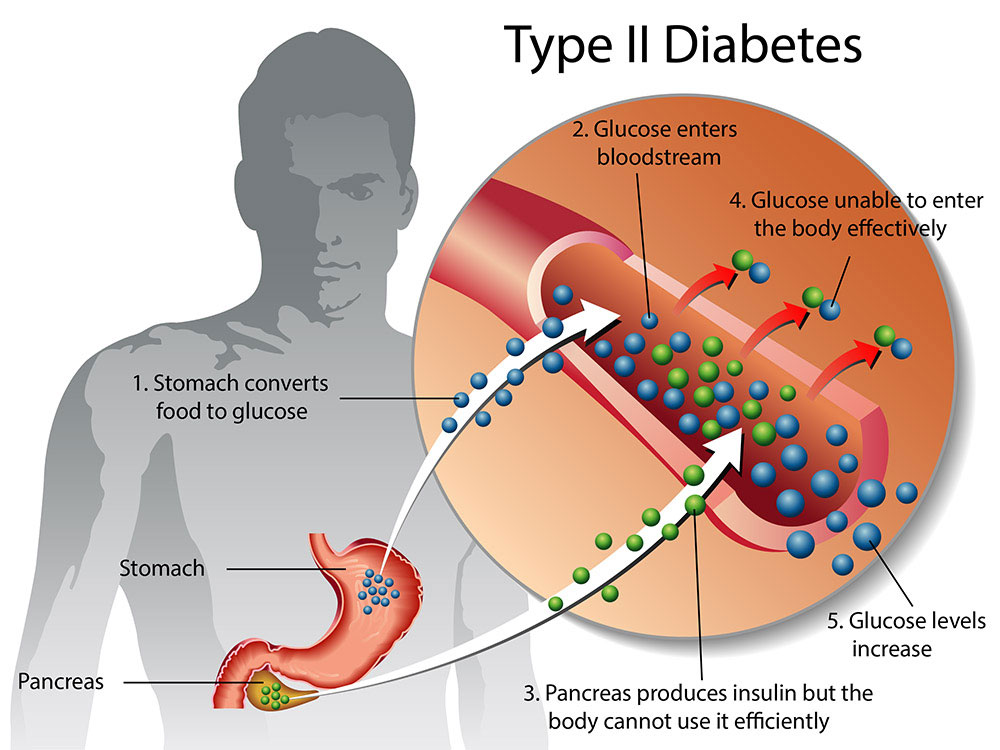

Modern society has a limitless availability of food and a day-night rhythm which is disrupted due to irregular patterns of sleep activity and frequent artificial light source exposure. Individuals in Western countries also have a tendency to distribute their daily consumption of food over 14 hours, which is likely to lead to the lack of a proper nighttime fasting state.

These are all contributing factors to type 2 diabetes development which has become a common worldwide metabolic disease, estimated by the WHO to result in over 1.5 million fatalities every year.

Time-restricted eating is a method for metabolic health improvement and is designed to counteract daytime eating’s harmful effects by restricting food consumption duration and restoring the daytime eating cycle and prolonging the evening and nighttime fasting period.

Prior research has shown that time-restricted eating results in encouraging metabolic changes in obese or overweight individuals, such as better insulin sensitivity, reduced blood sugar levels, and increased fat burning; but these effects haven’t been examined in detail. Also, although these results are encouraging, these studies made use of significantly short eating time frames of 6 to 8 hours, and study settings that were highly controlled, which makes such regimens challenging to incorporate into everyday life.

Time-restricted eating is occasionally followed by unintended loss of weight that would be likely to improve metabolic health, yet these improvements in metabolic health have also been observed without weight loss, suggesting that other mechanisms are involved in how metabolism is affected by time-restricted eating.

Metabolic health impaired individuals experience metabolic process rhythm changes in comparison to healthy, lean people and the researchers put forward that a disturbed eating-fasting cycle plays a part in these metabolic rhythm impairments. The researchers suggest that restricting the consumption of food to only daytime and prolonging the nighttime fast duration could be beneficial to metabolic health.

The study involved 14 people with type 2 diabetes between the ages of 50 and 75 years and a BMI of 25 kg/m2. The study was comprised of two intervention periods of 3 weeks: a time-restricted eating period and a control period, separated by a wash-out duration of a minimum of 4 weeks.

The body weight of the individuals was measured at the beginning of each intervention and they were equipped with a glucose monitoring device that continuously measured blood sugar levels every 15 minutes. The individuals were told to adhere to their normal physical activity and sleep patterns and to keep a stable weight. A sleep and food diary completed throughout the first intervention was made use of for ensuring that diet throughout the 2nd period was similar in both quality and quantity.

Throughout the time-restricted eating period, individuals were told to consume a normal diet within a 10-hour frame throughout the day and to finish consuming their food no later than 6 PM. They were allowed outside this time frame to consume black coffee, plain tea, or water, with moderate consumption of zero-calorie soft drinks throughout the evening also permitted. Participants were only required to distribute their normal food consumption without any other restrictions over 14 hours during control.

The eating frame for time-restricted eating was an average of 9.1 hours in comparison to 13.4 hours in control, with sleep-wake patterns comparable in each case with sleep duration of 8.1 hours and 8.0 hours on average. Average body mass of participants was similar at the beginning of both time-restricted eating and control and though they were told to maintain a stable weight, a small but significant weight loss took place in response to time-restricted eating but not control.

Time-restricted eating was shown to reduce 24-hour glucose levels, mostly because of a reduction in nighttime blood sugar, and the normal blood glucose range duration increased to 15.1 hours on average as opposed to 12.2 hours throughout the control phase. The time-restricted eating group had consistently lower morning fasting glucose levels compared to the control diet group, which could be due to lasting changes in nighttime glucose control.

Low blood sugar duration wasn’t significantly increased by time-restricted eating and there were no reports of serious negative effects as a result of the regimen, showing that an eating frame of about 10 hours is an effective and safe lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes individuals.

Liver glycogen levels were evaluated in the morning about halfway through each intervention after the 10-hour or 14-hour night-time fasting period with measurements taken at the end of each study period again following an 11-hour fast for both time-restricted eating and control. Liver glycogen didn’t differ significantly between time-restricted eating and control in both cases, and liver fat analysis revealed no difference in their composition or quantity between interventions.

As opposed to a prior study into time-restricted eating, this one didn’t demonstrate that the regimen had any impact on insulin sensitivity. The earlier study had however made use of a much shorter 6-hour food consumption frame with the last meal being eaten at 3 PM. This led to a longer fasting period that could be more effective but would be impractical to integrate into the lifestyle of most type 2 diabetes individuals.

In conclusion, the researchers say that a 3-week daytime 10-hour time-restricted eating regimen reduces glucose levels and extends the normal blood sugar range duration in type 2 diabetes individuals in comparison with distributing daily consumption of food over a minimum of 14 hours.