Approximately 80% of older individuals suffer from hypertension. Having healthy blood pressure can safeguard against serious disorders such as strokes, heart attacks, and heart failure.

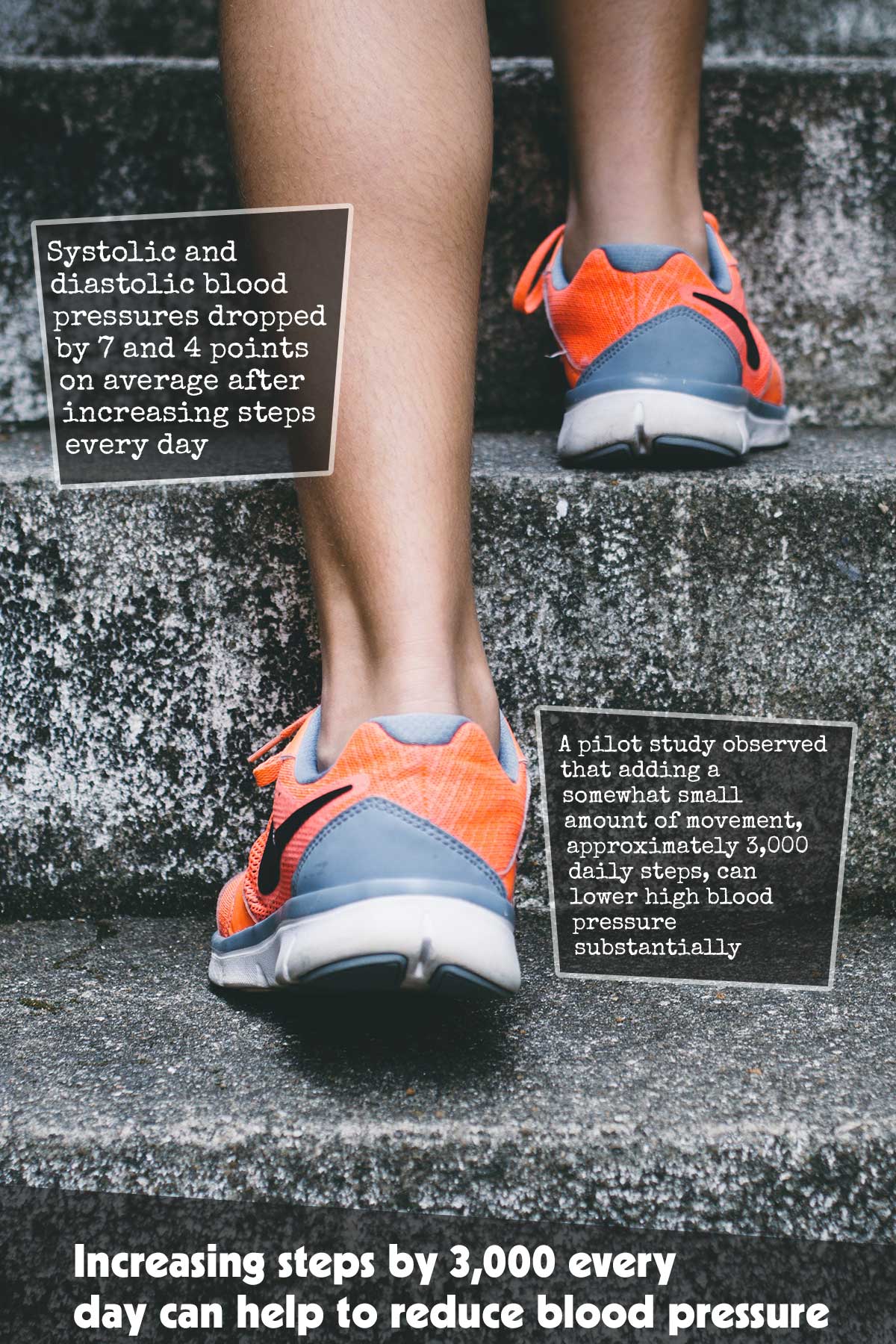

A pilot study observed that adding a somewhat small amount of movement, approximately 3,000 daily steps, can lower high blood pressure substantially.1✅ JOURNAL REFERENCE

DOI: 10.3390/jcdd10080317

This study wanted to find out if older individuals with high blood pressure could achieve these benefits with a moderate increase in walking every day, which is one of the most common and easiest types of physical activity for any individual.

Walking is easy to do, no equipment is needed, and it can be done anywhere at pretty much any time.

The research focused on a group of inactive older individuals between 68 and 78 years who walked approximately 4,000 steps every day on average before the research.

After consulting current studies, it was established that a reasonable goal would be a 3,000 step increase, 3,000 steps are enough but not too demanding to attain for health benefits.

This would also place most individuals at 7,000 steps every day, consistent with the American College of Sports Medicine’s advice.

The study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning everything had to be done remotely.

The participants were sent a kit with blood pressure monitors, pedometers, and step diaries for logging how many daily steps they were walking.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures dropped by 7 and 4 points on average after increasing steps every day.

Other research suggests blood pressure reductions such as these correspond to a reduction of 16% in cardiovascular mortality risk, an all-cause mortality risk by 11%, an 18% reduction in heart disease risk, and a 36% reduction in stroke risk.

It’s remarkable that a basic lifestyle treatment can be as effective as some meds and structured exercise.

The results indicate that the 7,000-step program the individuals in the study accomplished is comparable to reductions achieved with anti-hypertensive meds.

Out of the 21 participants, 8 of them were already taking anti-hypertensive meds. Those individuals still experienced systolic blood pressure improvements from increasing their activity every day.

The researchers found in a previous study that exercise combined with meds improved the effects of blood pressure meds on their own. It demonstrates exercise’s value as an anti-hypertensive treatment. The effects of the meds are not completely negated; exercise is just part of the treatment strategy.

The researchers observed that walking in continuous bouts and walking speed didn’t make a difference as much as just increasing total steps.

They observed that the physical activity volume is most important and not so much the intensity. Making use of the volume as a target, whatever works and fits in will provide health benefits.